Walkers at dawn

Clàudia Pujol

Journalist

With two buses donated by the Barcelona City Council after being taken out of service in the Catalan capital, a pilot school transport project seeks to improve access to education in rural areas of northern Senegal. Promoted by ORU Fogar, the initiative aims to reduce absenteeism and school dropout rates by addressing the long walking distances and insecurity that thousands of students face every day. Once all the planned buses are fully operational, the project will connect 87 villages, easing the journey to the classroom for more than 6,000 students in the Department of Dagana.

Before the sun has broken through the morning mist, the great migration begins on the road linking Ross Bethio and Gae, in northern Senegal. From six o’clock in the morning onwards, thousands of children and young people leave their homes, which are made of mud or cement and topped with straw or metal roofs. They begin walking through rice fields and laterite soil until they reach the main road. It is a daily, silent choreography of backpacks resting on fragile shoulders, multicoloured uniforms and sandals kicking up dust as they move. Their destination is school or secondary school. They walk alone, in pairs or in small groups, but almost never accompanied by an adult. In rural Senegal, walking between three and twenty kilometres a day is the everyday toll paid in order to receive an education.

In this region crossed by the Senegal River, which winds like a silver belt across the plain, villages blend into the surrounding landscape. When it rains, the paths turn muddy and impassable. When the sun burns overhead, dust rises like a cloud, covering everything in shades of ochre and red. At moments when exhaustion outweighs caution, some students raise their arms to hitchhike. Sometimes a car stops. Sometimes it does not. Getting in involves risks, especially for girls.

Classes begin at eight in the morning. Arriving late is common. And trying to follow a lesson already underway is like fighting a battle lost before it has even begun.

A young country, a fragile education system

Senegal is one of the youngest countries in the world: more than 40 per cent of its population is under the age of fifteen. Schooling is compulsory between the ages of six and sixteen, but the law often collides with geographical and social realities. In rural areas, distance, poverty and domestic responsibilities force thousands of boys and girls to abandon their studies prematurely. Some reports by the World Bank, UNESCO or UNICEF make for uncomfortable reading: seven out of ten ten-year-olds cannot read or understand a text appropriate for their age. Seven out of ten also lack basic numeracy skills. Failure and school dropout accumulate as students progress through the education system, turning secondary education into a desert. In this context, physical access to educational centres is as decisive as the curriculum itself. The struggle for education does not begin with the first book, but on the road.

The pilot test: two buses from the “City of Barcelona”

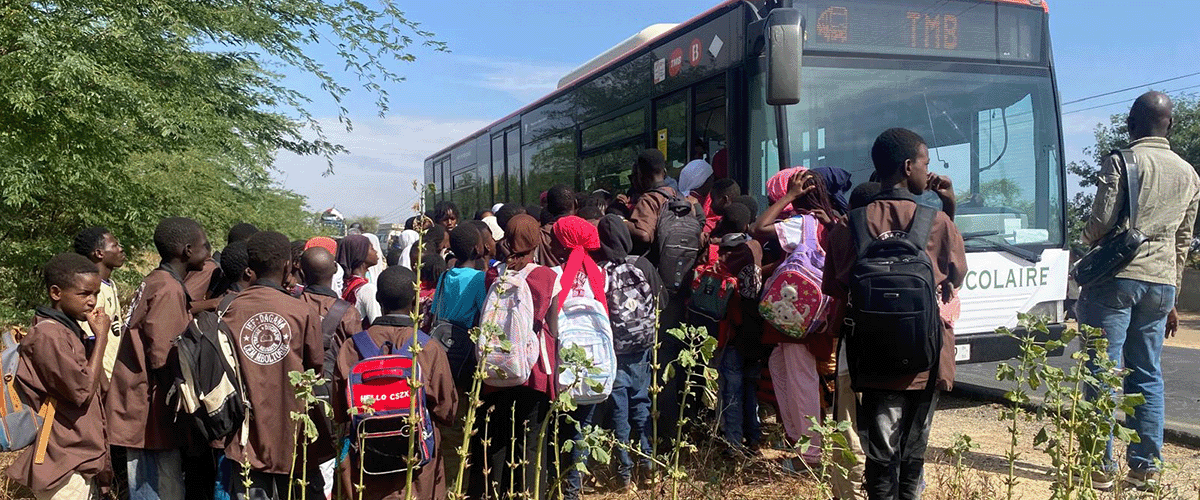

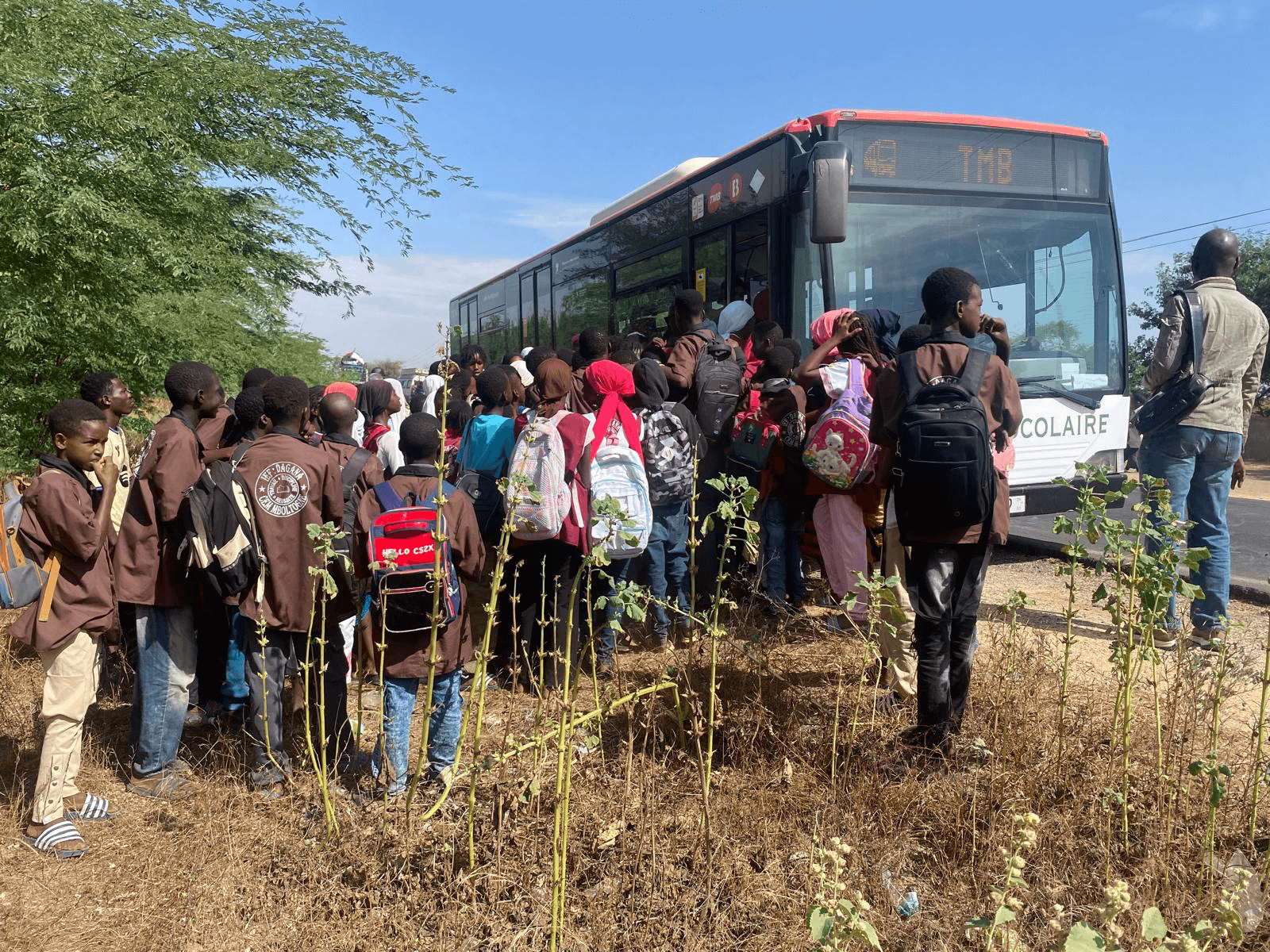

Today is a different day. Before seven in the morning, on the main road in Dagana, alongside the carts, bicycles and battered cars that form part of the everyday landscape, a white-and-red bus appears in the distance. It bears the TMB (Transports Metropolitans de Barcelona) logo and large letters reading Transport Scolaire. It moves slowly, raising a curtain of fine dust, and stops wherever it spots a group of children with backpacks on their shoulders.

This is a pilot test. In a few weeks, the service will operate on a regular basis. Today, there are no strict timetables and no fixed stops. The driver brakes whenever he sees children walking along the road. The doors open. Boys and girls climb aboard with a mixture of euphoria and disbelief, as if that simple gesture of sitting down, looking out of the window and leaving the road behind were a small revolution.

Ourey is nine years old and walks six kilometres every day with her friends to get to school. Babakar is twelve and wears a Real Madrid shirt that is clearly too big for him. Like Fatou, thirteen, who looks at us with a contagious smile, they cover between seven and eight kilometres a day. They prefer walking to getting into cars driven by strangers. “Here, during childhood, you learn with your feet,” the driver remarks. Ousseynou is twenty years old and is training to become a construction technician. “Between my house and the vocational training centre there are seventeen kilometres. Hitchhiking is my only way of getting there,” he tells us.

Along with the students, several journalists from Senegal’s leading media outlets also board the bus. They want to report on the launch of a project that began to take shape two years earlier, more than four thousand kilometres away.

Invited by ORU Fogar, the President of the Dagana Departmental Council, Ababacar Khalifa Ndao, visited Barcelona in November 2023. An intensive programme of meetings was organised for the visit, involving civil society organisations, development cooperation actors and various departments of the Government of Catalonia and Barcelona City Council. It was during one of these meetings with municipal officials that the conversation turned to a problem that is as simple as it is structural: the difficulty students face in reaching schools and secondary schools in rural areas.

From that realisation emerged the proposal to reuse buses withdrawn from service in Barcelona — in the Catalan capital, vehicles are retired after ten years of operation — to implement a school transport system in northern Senegal that could help improve schooling conditions. The transfer of the buses was formalised on 23 January 2025 at an institutional ceremony held in Barcelona, attended by the city’s mayor, Jaume Collboni.

From the signing of the agreement to the pilot test involving two buses, numerous bureaucratic hurdles had to be overcome. “From winning the public tender launched by Transports Metropolitans de Barcelona, which was initially very reluctant to donate vehicles, to the problems encountered at customs in the Port of Dakar,” explains Carles Llorens, Secretary General of ORU Fogar. “But once all the buses required for the project are in Dagana — because we are working to secure more donations — eighty-seven villages will be connected, positively impacting the daily lives of more than 6,000 primary and secondary school students, over 2,500 of whom are girls.”

Dagana: a long way to school

Dagana is a department which, beyond primary schools, has thirty-nine secondary and upper-secondary schools, five vocational training centres and an ISEP (Richard-Toll Higher Institute of Vocational Training), serving a student population of 38,000 spread across rural, peri-urban and urban municipalities.

The collège in the town of Mboltogne brings together four hundred and twenty-seven students crammed into small barracks, taught by teachers who combine vocation and fatigue in equal measure. There are only a few minutes left before classes begin, and everything is haste and shouting in French and Wolof.

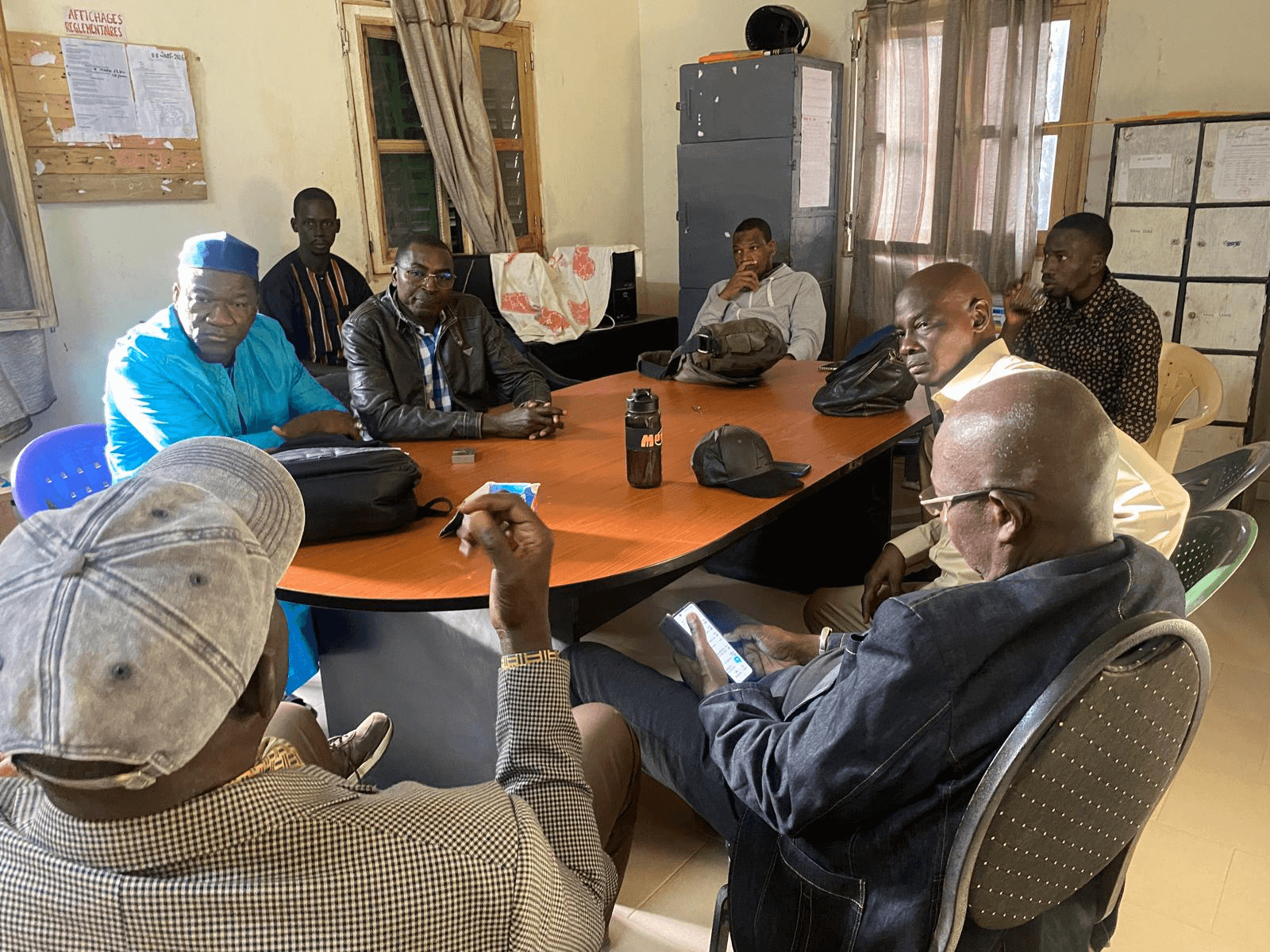

The teachers’ room where we’re meeting is a rectangular space, lit by natural light filtering through two windows with thin curtains half drawn. The walls, a faded yellow, are dotted with cork boards covered in administrative notices, printed sheets and documents pinned in place. The furniture is austere: a worn metal cupboard, shelves stacked with folders and a side blackboard filled with notes. Everything conveys a sense of permanent provisionality, but also of constant use. At the centre of the room, a large wooden table hosts an improvised meeting between the President of the Dagana Departmental Council, Ababacar Khalifa Ndao, the Secretary General of ORU Fogar, Carles Llorens, the school’s headmaster, Mr Bakhoum, and other education officials. All of them sit on mismatched plastic chairs and celebrate the launch of the two buses sent from Barcelona. Nevertheless, it is necessary to design a structured pick-up plan that can benefit children and young people living in villages within rural communities located a half-hour walk from the paved road.

“In Dagana, distance is a form of exclusion,” the headmaster sums up. “It’s not that families don’t want to educate their children; it’s that the journey is long and exhausting even before the school day begins. School dropout is not a sudden decision, but the result of cumulative wear and tear. A few minutes of lateness every day turn into days and weeks by the end of the year. And occasional absences from school become a gradual disengagement.”

“Climatic conditions don’t help either,” one of the teachers continues. “We move from the intense heat and sand-laden winds of summer to the bitter cold of winter. On top of that comes the lack of school canteens and the difficulty of finding host families for those who live far away.”

“Parents also complain about insecurity and the sexual assaults their daughters suffer on the way to school,” adds one of the education officials. “In fact, the most critical period is between the ages of twelve and sixteen, when secondary school is simply too far away.”

“Clearly, two buses will not reverse an endemic problem or replace public policies that fail to reach the periphery, but they do point the way forward,” the headmaster concludes.

A way forward that certainly does not arrive on a high-speed train, but that perhaps begins, very tentatively, when a bus from Barcelona opens its doors at dawn and simply says: get on!